Wednesday, March 24, 2010

The Glacial Era

The modern drainage pattern for the region includes a watershed that encompasses both peninsulas of Michigan, western Wisconsin and Minnesota and the extreme northern portions of Indiana, Ohio as well as the New York panhandle and Southern Ontario. All rivers and streams in these areas drain into the Great Lakes. From the lakes they flow through the St. Lawrence River and into the Atlantic Ocean.

The water from Lakes Superior and Michigan both flow into Lake Huron through the St. Mary's River (Superior) and the Straight of Mackinaw (Michigan). This water in turn flows into Lake Erie through the St. Claire and Detroit rivers. This also includes the water from the Georgian Bay. Lake Erie drains through the Niagara River into Lake Ontario and then out into the Atlantic Ocean through the St. Lawrence River.

Before the advance of the Wisconsin glacier, the flow of water from the region followed much the same course as it does today. The major difference between the two is in the connection between Lakes Huron and Erie and the St. Clair and Detroit Rivers. Before the ice advance, the water from the current Superior, Michigan and Huron basins flowed into the area now occupied by the Georgian Bay off Lake Huron. All of the water from the current Lake Huron area, south to Lake St. Clair, flowed into this waterway. From there it flowed through the area now occupied by the Trent River to the Bay of Quinte on Lake Ontario ).

The southeast portion of Michigan and Northern Ohio and Indiana were drianed by the preglacial Erigan River that flowed over the land currently occupied by Lake Erie, over the Niagara Escarpment and through the area of Lake Ontario where it merged with the water from the upper portion of the basin and then out to sea through the ancestral St. Lawrence basin.

For more information click here (Great Lakes Atlas)

The Great Lakes, a resource often abused, misused and rarely appreciated.

Because of the large size of the watershed, physical characteristics such as climate, soils and topography vary across the basin. To the north, the climate is cold and the terrain is dominated by a granite bedrock called the Canadian (or Laurentian) Shield. (Precambrian rocks under a generally thin layer of acidic soils). Conifers dominate the northern forests.

In the southern areas of the basin, the climate is much warmer. The soils are deeper with layers or mixtures of clays, silts, sands, gravels and boulders deposited as glacial drift or as glacial lake and river sediments. The lands are usually fertile and can be readily drained for agriculture. Much of the original deciduous forests have given way to agriculture and sprawling urban development.

Although part of a single system, each lake is different. In volume, Lake Superior is the largest. It is also the deepest and coldest of the five. Superior could contain all the other Great Lakes and three more of Lake Erie. It is situated not far from the centre of the continent of North America.Its greatest length is from east to west, about 355 miles, and its greatest breadth is about 160 miles.It is interesting to note that in Minnesota one of the branches of the Mississippi River approaches to within twenty miles of the western extremity of Lake Superior, and a small lake near the head of the Albany River, which flows into Hudson's Bay, is only four miles from a bay on the northern shore. Because of this short distance to portage it was used by the Hudson's Bay Company to transport goods north.

The country around Lake Superior is bold and hilly, with the exception of the peninsula between it and Lake Michigan, but few of the hills rise above 1000 feet. On the southern shore are the Pictured Rocks. These rocks are gray and red sandstone, from 100 to 200 feet high, in many places presenting fantastic figures, and marked by numerous stripes of Yellow and red.

The around this lake are very old, being mostly Laurentian and Huronian. The Huronian rocks are composed of conglomerates, green stone, shale, quartz-ite and limestone. For this reason there are vast deposits of useful minerals for which this region is noted. The minerals are principally copper and iron ore on the south side of the lake.

Lake Michigan, the second largest, is the only Great Lake entirely within the United States. It is 320 miles long and 70 miles in mean width. I t receives the waters of numerous rivers and is connected by a canal with the Mississippi River. Lake Michigan is among the most urbanized areas in the Great Lakes system. It contains the Chicago, Milwaukee and Grand Haven metropolitan areas. Its dangerous shores are lighted by a large number of lighthouses.This region is home to about 8 million people or about one-fifth of the total population of the Great Lakes basin.

Lake Huron, at its northern extremity receives the waters from Lake Superior through the Sault Ste. Marie, and also those of Lake Michigan through the Straits of Mackinac. At the southern extremity its waters flow out through the St. Clair river, Lake St. Clair and the Detroit river into Lake Erie. Georgian Bay is separated from Lake Huron by the peninsula of Cabot's Head on the south and by the Manitoulin islands on the north, and north of these islands is Manitou bay, or the North channel. The entire width of Lake Huron, including Georgian Bay, is about 190 miles, and its length is about 250 miles. It is the third largest of the lakes by volume. The principal streams from Michigan, which flow into Lake Huron are the Thunder Bay river, the Au Sable and the Saginaw, and, from Ontario, the French, the Muskoka, the Severn and the Nottawasaga, all flowing into Georgian Bay, and the Saugeen, the Maitland and the Au Sable. Many Canadians and Americans own cottages on the shallow, sandy beaches of Huron and along the rocky shores of Georgian Bay.

Lake Erie is the smallest and is the most southern of the five Great Lakes. At its southwest extremity it receives the waters of the three upper lakes, Superior, Huron and Michigan through the Detroit river, and at its northeast extremity it discharges its waters by the Niagara river into Lake Ontario. It is exposed to the greatest effects from urbanization and agriculture. Because of the fertile soils surrounding the lake, the area is intensively farmed. Seventeen metropolitan areas with populations over 50,000 are located within the Lake Erie basin. Although the area of the lake is about 26,000 km2 (10,000 square miles), the average depth is only about 19 metres (62 feet). It is the shallowest of the five lakes and therefore warms rapidly in the spring and summer, and frequently freezes over in winter.

Lake Ontario, the lowest and the smallest of the five Great Lakes, lies between New York and Canada. The name, Ontario, in the Indian language, means beautiful. The lake is about 180 miles long from east to west, and its average breadth is about 35 miles. Although slightly smaller in area, is much deeper than its upstream neighbor, Lake Erie, with an average depth of 86 metres (283 feet).

Monday, May 05, 2008

The First Welland Canal at Port Dalhousie 1829-1844

After the War of !8!2, the political structure of Upper Canada was in a state of transformation from the benevolent, paternalistic legacy of John Graves Simcoe, and his predecessors, to one in which men faced the problems of how the colonies should govern themselves and yet retain an allegiance to a wider empire. Coupled with a growing economy, an expansionist neighbour to the south and cultural differences between Upper and

Such was the case in the year 1818 when William Hamilton Merritt owner of a number of mills, and other businesses, on the Twelve Mile Creek, near what is now

On September 18, 1818 Merritt, and two of his friends, mill owners George Keefer and John Decew, mounted their horses and set off seeking a new supply of water. Merritt had borrowed a water level from Samuel Becket, another mill owner, to do calculations using his limited surveying skills. Their prime objective was to detail the ridge that separated the Chippawa (

Their calculations wee not accurate but it was still believed that the cut through the ridge was the answer. In fact, they were convinced that the idea could be expanded into a canal that would make it possible for ships to pass from one lake to another, opening a new route to the west.

The route would then follow the Twelve Mile Creek, which emptied into

Settlement of Port Dalhousie during this time consisted of a few homes built on the west side of the valley. The first families to settle around the Twelve Mile Creek lakefront entrance and shoreline were the United Empire Loyalists. The early settlers who arrived were faced with many hardships and met with much misfortune in attempting to clear and cultivate the land, build homes for their families and establish businesses. It was a constant battle filled with tragedy and suffering, often resulting in the loss and abandonment of hope.

Canals were a hot topic at the time, and only the previous year Merritt had stated the advantages for

The aim of Merritt's survey was to determine how deep a cut was needed to allow

Although it not easy to be precise in determining when, and by whom, the idea to connect the waters of

The prospect of connecting

Flowing down the escarpment are a number of small creeks, one of which is the Twelve Mile Creek. Merritt chose this creek to focus on because its source was near Allanburg. From there across the ridge to the

The escarpment and these few miles of high ground were the only obstacles to establishing a connection between Lakes Ontario and

With this information the first petition was sent to the Legislature on

As the economy improved in

Merritt’s suggested route was not automatically adopted by the Government. Under the Act commissioners were appointed, called “commissioners of internal navigation”, who were to “explore, survey and level the most practical routes for opening communication by canals and lakes between Lake Erie and the eastern boundaries of the Province.”

The route preferred by these commissioners for the canal from Lake Erie to Lake Ontario commenced on the Grand River, or any other convenient point on Lake Erie, and leading to Burlington bay, at the head of Lake Ontario, the considerations being that this route began at a point, which at all seasons of the year had plenty of water to feed the canal, that it was sufficiently remote from the frontier, and that it was free from ice from three weeks to a month earlier than a point near Fort Erie. Burlington bay was preferred for the outlet of the canal, because it was a fine basin, large and deep, capable of sheltering the whole Royal Navy of Great Britain, that it also was sufficiently remote from the frontier, had a strong military position, was surrounded by a populous and highly cultivated country, and seemed destined by nature to be the center of a flouring trade.

The outlet from Burlington bay into Lake Ontario, the Burlington Bay Canal, suggested by the commissioners, was undertaken at the public expense, and although it was not intended as a part of the project of the canal, yet, as it would render the port accessible, it was considered a work of great value to the tract of country lying to the west.

The survey of the route between

The locks were to be 100 feet long and 22 feet wide in the clear. A canal of these dimensions, it was thought, would accommodate vessels of 80, or even 100, tons, and by enlarging the locks to the proper size the large class of gun brigs light might go through, and even steam vessels in emergencies. In connection with this project the commissioners said:

"The superior advantages attending such a canal, as is here proposed, would destroy the hopes and defeat the calculations of the commissioners of the American canal; as our being enabled to ship commodities on the Grand River three weeks before the lake opens at Fort Erie and Buffalo, with a certainty of their being transferred without removal direct to Montreal, would give a preference to that route, and our trade with much of that from the south shore of Lake Erie would thereby be secured to us."

The Board of Commissioners, after much survey work on this route, recognized that this route, largely due to cost, was impractical.

The committee made its report in 1823, the result of which was the incorporation of a private company, organized in 1824 and named the Welland Canal Company. This company proposed to establish the necessary communication between the two lakes by means of a canal and railroad. They intended running up the Welland river, passing across the township of Thorold, tunneling through the high ridge of land about a mile and a half, then proceeding directly by a canal to the brow of the hill or highland, and then by a railway down to the lowland, and connecting by another canal with the navigable waters of Twelve Mile creek, so as to afford the desired egress to Lake Ontario. The canal was to be of a capacity to accommodate "boats of not less than 40 tons."

Public meetings were held, surveys made, and other steps taken to excite public interest in the enterprise; but notwithstanding all this, upon the day of breaking ground for the beginning of the work,

Monday, December 31, 2007

"CANALLERS"

Before the St. Lawrence Seaway opened, a type of ship, long familiar on the St. Lawrence River and in the Great Lakes was known as the "Canaller" and was the result of the difficult geographical features of the St. Lawrence River and the limitations of the canals built to overcome these difficulties. Canallers were divided into three main categories; bulk, package and special freighters.

The water route from the lakehead to the open sea is divided into three main parts; open water, navigation on the lakes themselves, river and canal navigation on the upper St. Lawrence River between Kingston and Montreal, and almost unrestricted navigation on the lower St. Lawrence and the Gulf. The upper St. Lawrence section is, of course, the portion most closely associated with the canaller and the part which has restricted free navigation

Although there were considerable improvements to the canals over the years, they still imposed many restrictions on design, and the "Canaller" was the result of the compromises made by these restrictions and the cargo-carrying requirements.

The canal locks on the three main sections of the St. Lawrence Canals varied slightly in dimensions, those of the Soulanges section being a little wider and longer than the Lachine and Cornwall - Lachine and Williamsburg sections. The controlling lock of the whole system, as far as ship dimensions are concerned, was No. 17 at Cornwall.

Canaller "ALGONQUINS tied up in the fourth Welland Canal

The maximum breadth of canallers was therefore strictly controlled by this lock and is generally 43 ft 7 in. extreme at the bilge.

The maximum over-all length was also fixed. The deck outline was arranged to give a reasonable clearance for the swing of the gates. The normal depth over the sills restricted the draft to 14 ft and most canallers are designed to operate at this draft when canalling.

"C.W.CADWELL in for repairs at Muir Bros. Dry Dock in Port Dalhousie, Ontario

Wednesday, February 21, 2007

STORIES OF THE GREAT LAKES

Ontario - First Steamboat on the Great Lakes

Excerpts from an article by RICHARD PALMER published in “FreshWater” A Journal of Great Lakes Marine History Volume 2 Number 1 Summer 1987

The steamboat ONTARIO by J. Van Cleve 1826 (Courtesy of the Jefferson County Historical Society, Watertown, New York)

Shortly after the end of the War of 1812 a group of enterprising businessmen from northern New York state, decided to build what appears to have been the first steamboat on the Great Lakes at Sackets Harbor. Steam navigation had proven itself on the Hudson River and the relatively open waters of Long Island, and it was thought it could be as successful on the Lakes.

After many attempts to incorporate a company and a series of ownersand investors, preparation for the construction of the Ontario finally began. The Ontario was built after the model of the Sea Horse, then running on Long Island Sound. It was no' x 24' x 8', registered at 237 tons.

The ship carpenter was Ashel Roberts, It was equipped with a low pressure cross-head beam engine built at the works of Daniel Dod in Elizabethtown, New Jersey.? The boilers were 17 feet in length and three and a half feet in diameter. The engine cylinder was 20 inches in diameter and had a three-foot stroke. The paddlewheels were n feet, 4 inches in diameter and the engine was rated at 21 horsepower. The rigging consisted of three fore-and-aft gaff sails.8 By the fall of 1816, the cast hubs for the paddlewheels for the Ontario had been ordered.

According to the original enrollment dated at Sackets Harbor April 11,1817, Francis Mallaby was Master

The steamboat Ontario by J. Van Cleve 1826, (Courtesy of the Jefferson County Historical Society, Watertown, New York)

The exact date the Ontario made its maiden voyage was critical to determine the long-standing claim that she was indeed the first steamboat to sail on the Great Lakes. It was found in the Ontario Repository, a newspaper published in Canandaigua, New York. The article is in the form of a letter written from Sackets Harbor on April 22, 1817:

"The Steam Boat Ontario on Wednesday last [April 16] left this port for the first time, in order to try the force of her machinery. A number of Gentlemen, ambitious to be among the first that ever navigated the waters of Lake Ontario in a Steam Boat, embarked on board.

"She started from the wharf, accompanied by an excellent band of music, greeted by the huzzas from the people on the adjacent shores and the U.S. brig Jones.

"The novelty of the spectacle had drawn together a large crowd of spectators, whose curiosity was amply satisfied by the rate of speed exhibited, full equal in the opinion of many, to any of the North River Boats. The accommodations on board are excellent, as no pain or expense has been spared by her owners, in her construction or equipments. The facility with which the lake can now be navigated, will add new inducements to its commerce—that of the river St. Lawrence: Travellers whose curiosity may lead them to nature's grandest scene, the Falls of Niagara, will be convinced, hereafter pursue the route to Sacket's Harbor and thence proceed in the Steam Boat.

"From New-York to Niagara in the steamboats and stages; this route will be performed in five days; a much shorter period than the average passages were formerly made from New-York to Albany. Such is the revolution that steamboats have effected in travelling with a few years. We wish much encouragement and success to the projectors of so useful an undertaking."

In fact, the Ontario Repository had already reported that "In passing out of the mouth of the Genesee River, on Saturday, we are informed, she had one of her wheels broken, being near the point, in a heavy sea." This incident occurred during the vessel's maiden voyage. Like all previously built steamers, the shaft on which the paddlewheels were mounted rested by its own weight in unsecured boxes. The action of the waves soon lifted the shaft which tore the wheel coverings to pieces and damaged the paddlewheels.

Captain Mallaby hoisted sail and immediately brought her about to return to Sackets Harbor for repairs. The shaft was then properly secured by bolting of boxes and bearings under the outer ends. This event was the only thing that marred that had been quite an experience for those aboard.

Everywhere the Ontario went she was met with much fanfare. When she arrived at Oswego, school classes were dismissed and there was a big celebration. Bells pealed and cannon roared.

The steamboat attempted to make weekly trips between Ogdensburg and Lewiston. However, she rarely exceeded six knots per hour. On July 1, 1817, the owners advertised in local newspapers that, finding the 6oo-mile round-trip impossible to accomplish in a week, the voyage would be extended to 10 days. The round trip fare was $15.

In the spring of 1818, the Kingston Gazette reported the grounding of the vessel in Oswego. "Sackets Harbor, May 19. The steamboat Ontario, which was (in a recent storm), driven on a ledge of flat rock near Oswego, has been got off, and arrived here this morning. We are happy to learn also, that the damage done her is inconsiderable to what has been currently reported. It is expected she will be ready for further operations in a week, or fortnight at the farthest."

In spite of this mishap, operation of the steamboat quickly returned to normal.

"Steam Boat Ontario”—This fine boat continues to ply most successfully between Ogdensburg and Lewiston. It is well fitted up, and notwithstanding the unfortunate accident that occurred early in the season and the many prejudicial and unfounded reports propagated, receives very liberal patronage and rides the lake with perfect ease and safety.

An advertisement gives some interesting details of operation of the Ontario. Going up, the vessel left Ogdensburg at 9 a.m. Saturday, 3 p.m. Sunday from Sacket's Harbor, and 3 p.m. Monday from Hanford's Landing [port of Rochester]. Going down, it departed from Lewiston at 4 p.m. Tuesday, Hanford's Landing at 4 p.m. Wednesday, and from Sacket's Harbor at 4 p.m. Thursday. The fares were $5 from port to port, and steerage passengers (without board,) $2.50, Freight and families moving were carried "as reasonably as in other vessels."

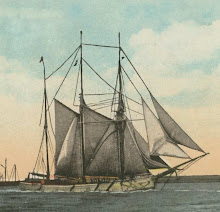

Operating in conjunction with the steamboat was the schooner Kingston Packet which had shallow enough draught to enter the ports where the steamboat could not tie up, such as Oswego and Pultney ville. The schooner was "provided as a tender" for the Ontario, and was labeled a "fast sailing craft".

Apparently the Ontario was not as a profitable venture as its owners intended it to be, as it was sold by a decree of Chancery at Sackets Harbor on May 8, 1824, to Jesse Smith of Smithville, a small rural community near Sackets Harbor. Luther Wright, later a prominent banker in Oswego, was captain and clerk, and Judge Hawkins of Henderson, also near Sackets Harbor, was sailing master.^

Since Ontario had always plodded along at five or six miles per hour, her owners decided to put a more powerful engine in her. Accordingly, in the winter of 1827-28, the square engine then in the steamboat Martha Ogden (owned by the same parties) was installed in the Ontario at Hanford's Landing. However, for some reason, this re-engining of the Ontario was not successful.

The career of the Ontario continued to be eventful. In 1829, while under the command of a Captain Hitch, an old whaler from New Bedford, she was caught in a storm some 25 miles below Niagara. She was brought to anchor to ride out the storm. After holding most of the day and night, she began to drag anchor, to avoid going ashore, being in four fathoms of water, the cable and anchor were slipped.

Although the existence of the Ontario was relatively short, by freshwater standards she was around for a long time... some 14 years. Many vessels came and went in that period. Also, as improvements were made these pioneer steamboats generally became quickly obsolete. A good schooner could make better time than the slow moving Ontario, which was dismantled at Oswego in 1832. However, the Ontario still had carried the distinction of being the first steamboat to be "subjected to a swell" on the Great Lakes.

OWNERS AND MASTERS OF THE STEAMBOAT ONTARIO11 April 1817 Hunter Crane, Samuel F. Hooker, Elisha Camp, Melancthon T. Woolsey, William M. Sands, Jacob Brown and Charles Smyth, owners. Francis Mallaby, Master.

17 May 1819 Eri Lusher, owner. Peter Sexton, Master

20 Aug. 1820 William Waring, owner. William Vaughan, master.

19 Aug. 1823 William Waring, owner. Rovert Hugunin, master

2 May 1824 Jesse Smith, owner. Luther Wright, master.

i June 1825 Leonard Denison, owner. William Vaughan, master.

7 June 1827 Leonard Denison, owner. Peter Ingalls, master.

29 June 1828 Leonard Denison, owner. Patrick Wallace, master.

11 May 1830 Leonard Denison, owner. WR, Miller, master.

14 July 1831 Re-enrolled at Oswego. No names given.

Source: United States, National Archives, RG 41, Records of the Bureau of Marine Inspection, Master Abstracts of Enrollments Issued at Lower Great Lakes Ports, 1815-1911.

Other sources state her last owner were Enos Stone and Elisha Ely of Rochester.

Visit our Web Site for more stories and pictures on the history of The Great Lakes.

http://www.abouthegreatlakes.com